For more than six decades, centenarian Xu Yuanchong has applied his linguistic skills in Chinese, English and French to build literary bridges between the East and West, Yang Yang reports.

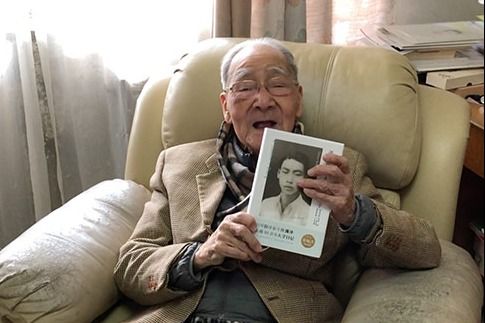

On April 18, prominent translator and professor of Peking University, Xu Yuanchong, celebrated his 100th birthday.

For decades, through translation, Xu has introduced not only French and English masterpieces into China, but also Chinese classical literature to the world in French and English.

He has not stopped working since starting his career decades ago, even when approaching his landmark birthday.

Born in 1921, Xu was admitted to the National Southwestern Associated University (Xinan Lianda) as a student of English language in 1938.At the university, among his teachers were prominent members of the literati, like Qian Zhongshu, and his fellow students there were people who would go on to achieve great things, such as Yang Zhenning, later a Nobel Prize-winner in physics.

Although the university only existed for eight years, it was a miracle in the history of education. In the middle of a war, the university, with elites drawn from Peking, Tsinghua and Nankai universities, educated much of the country's talent, maintained the cultural gene of the Chinese nation and preserved the kindling of Chinese civilization, says Bai Gengsheng, vice-chairman of the China Writers Association.

"And Xu Yuanchong is one of the excellent representatives of the university's graduates," Bai says.

In 1941, during the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-1945), Xu joined the army working as a translator for the First American Volunteer Group of the Chinese Air Force. In 1944, he entered the Institute of Foreign Literature Studies at Tsinghua University, studying plays by William Shakespeare and John Dryden. From 1948 to 1950, he studied plays by Jean Racine and Shakespeare at Universite de Paris.

Xu's love for translation was kindled when he studied at Xinan Lianda. His first work was the English translation of a love poem by Chinese architect and poet Lin Huiyin, which he deposited in the mail box of a girl he had a crush on. He fell in love with translation due to his favorite Chinese writer Lu Xun, who translated a lot of foreign works into Chinese.

In 1958, Xu started translating poems by Mao Zedong into English and French. But most of his translations were completed and published after 1983 when he started working at Peking University. He rose to prominence as a translator, becoming known as the only person who could translate Chinese, French and English classics in China.

In 1994, his translation, Song of the Immortals: An Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry, was published by Penguin Books. In 2010, China Association of Translation conferred upon him its lifetime achievement award. In August 2014, he received the FIT Aurora Borealis Prize for "outstanding translation of fiction literature" for "devoting his career to building bridges among Chinese, English and French-speaking peoples". He was the first Asian to receive this prestigious honor for translators since its establishment in 1999.

So far, he has published about 100 translated works in either Chinese, English or French, including Book of Poetry, Elegies of the South, Romance of Western Bower, Selected Poems of Du Fu, Selected Poems of Li Bai, The Red and the Black by Stendhal, Madam Bovary by Gustave Flaubert, In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust and Shakespeare Plays Vol 1. He is currently translating The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James.

Apart from his outstanding works, Xu is also famous for his thought and methodology on translation. Despite questions and doubts from his peers, he has been sticking to the principle that a translation should be beautiful in terms of sense, sound and form.

Recently, China Translation & Publishing House published the souvenir edition of Xu's works, including diaries he kept when he studied at Xinan Lianda, and his 21 translations of classical Chinese literature.

"We pay homage to Mr Xu, not only for his outstanding translation, but also his persevering pursuit of the meaning of life and truth, as well as his optimism, resilience and his love for translation," says Qiao Weibing, editor-in-chief of CTPH.

At the age of 86, Xu was diagnosed with cancer and given just seven years to live, but he conquered the disease. When his wife Zhao Jun died in 2018, he cried bitterly, but soon shifted his full attention back to translation. Even now, at the age of 100, he starts his work at 11 pm every day, and stops at 2 or 3 am. Sometimes he even works through the night.

"Xu's stories have inspired a lot of people. His life is full of legends and wisdom, and will continue to inspire more people," Qiao says.